William Shakespeare hated football.

In the early 1600s, Shakespeare’s play King Lear in Act 1, scene 4 used the phrase: “Nor tripped neither, you base football player.”

Which roughly translates as, “I won’t even let you be tripped [accidentally], you low-life football player.”

It was during a conversation between Kent, a follower of King Lear, verbally attacking Oswald, a servant of the king’s daughter Goneril. After hitting Oswald, Kent trips him and delivers the line as a further insult.

To be called a “football player” in the Middle Ages was not a compliment. It implied being low-class, brutish, and possibly dangerous.

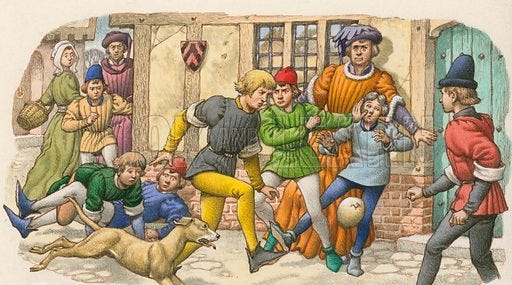

The sport has always been the global obsession that unites nations in support. But it hides a wild and untamed ancestor. The beautiful game bore little resemblance to its modern counterpart during the medieval era. There were no pristine pitches, no calculated passing sequences, no stadiums– what our ancestors called football was a wild spectacle known as “mob football,” something that could barely pass off as a sport, a street fight, and all-out war.

There were no lines demarcating the pitch in the Middle Ages of England, no whistles to tame the surging crowd, and no rules—instead, sprawling fields, bustling town squares, and even entire villages that morphed into chaotic battlegrounds. “Players,” if we could even call them that —weren’t merely players but entire communities – burly farmers, restless apprentices, and young men aching for some glory.

But in the middle of all the chaos, the goal was brutally direct: force the ball —often a rough-hewn animal bladder, to the opponent’s territory. There, the line blurred between victory and conquest.

But to claim this prize, tactics ranged from bone-shattering tackles to frenzied brawls and anything in between. Think flying elbows, trampling feet, and a wide range of shouts rising above the din. Broken limbs and battered windows were always collateral damage, but the thrill of this mayhem outweighed any concern for injury.

It was why the English monarchs had almost no patience for it.

King Edward II of England was the first to ban mob football in the year 1314, not so much out of sporting principle; he probably didn’t care, but to stop, or at least slow down, the rising tide of urban chaos the game created.

His decree spoke of the “great noise in the city caused by hustling over large balls,” which painted a vivid picture of this craziest sport unsettling the kingdom with its wild energy.

Most of the complaints were led by Merchants in London who saw it as a disruption to their businesses.

According to Jamie Orejan’s Football/Soccer: History and Tactics, the decree read;

“… which many evils may arise which God forbid; we command and forbid, on behalf of the King, on pain of imprisonment, such game to be used in the city in the future.”

Edward II’s ban barely made a dent. It turns out that football was way more stubborn than anyone figured. Just 35 years later, his son, Edward III, tried to finish what his father had started. Even though the new king had more authority amongst the people than his father did, he couldn’t completely get rid of the game and spent much of his 50-year reign fighting it.

But one of the reasons Edward III was intent on outlawing the sport was it became a distraction from practicing archery. The king restored England’s glory as a dominant military force in Europe and still one of the greatest Monarchs in its history, so mob football was in direct conflict with building a formidable army of skilled warriors, and archery was the backbone of the English army because it was mandatory.

In medieval Europe, the longbow revolutionized warfare, and Archers weren’t just seen as support units – they were the core of English armies. And so the weapon became synonymous with English military might. Mandatory archery practice from a young age made sure there was a ready pool of skilled archers for wartime, which created a strong deterrent against invasion.

But 128 years later, Edward IV sang the same old tune – football was just too distracting for archery.

In his decree, the king stated;

“No person shall practice … football and such games, but every strong and able bodied person shall practice with the bow for the reason that the national defence depends upon such bowmen.”

Richard II and Henry IV hopped on the “ban-wagon” for a while, and for almost two centuries, it was king after king trying (and somewhat failing) to boot the sport out of England.

The Tudor king Henry VIII also attempted to ban the game, despite being a lover of said game, who ordered what could be the first football boots in history in 1540. He wasn’t known for much other than drinking and womanizing with his six different marriages, but he gets credit for seemingly liking the game.

By the 1600s, nobody cared much about the game’s impact on archery. The problem was that the “matches” were straight-up riots, more like brawls than games. So, another round of bans started.

In 1604, Local authorities in Manchester complained that; “With football… there has been great disorder in our town of Manchester, we are told, and glass windows broken yearly and spoiled by a company of lewd and disordered persons.”

During a game in York in the winter of 1660, a church window saw the wrong end of a ball, and as punishment, the Mayor fined eleven of the players 20 shillings, which was a lot at the time. But all it did was trigger a full-blown riot that involved 100 armed men breaking into the Mayor’s house.

Turns out Edward II’s concerns were valid when he first tried to suppress the game 346 years earlier.

And that was the image the game presented for the next 300 years as it became even more popular.

Through the 1700s and 1800s, the fight wasn’t only about violence but image. Stuck-up types thought football was only for the lower classes, messing up their pretty ideas of order.

But just when you thought things couldn’t get worse, the early 1900s came along and outlawed women from playing the game. It was ‘too rough’ for ladies. It took until the 1970s for women to get back in the game.

Football has been an unyielding force throughout history, defied repeated bans thanks to its unwavering hold on the hearts of common people. From peasants to tradesmen, the thrill of the game resonated throughout every aspect of society.

The shared passion for it ultimately outweighed any edict from those in power. Eventually, the love for football permeated the highest levels of authority. Some kings did realise the futility of their restrictions, and they relented, their rigid opposition melted away into reluctant acceptance.

This appeal of football shows us the complexities of human nature—its potential for unity and chaos. In the turbulent aftermath of the English Civil War during the mid-17th century, the sport often became a catalyst for unrest. Fines and public shaming did very little to discourage rowdy players.

So in the late 19th century, football experienced a transformation. Order and structure took root, introducing rules and organizations that became the pillars of the beautiful game as we know it today, and it has thrived since.

Public schools began to embrace the sport while discouraging the violence that came with it, they introduced a structure. The structure came with rules, and as Britain expanded globally, football spread with it.